Effective risk management strategies are essential for every organization today. But what exactly is risk, and how can organizations quantify, prioritize and manage it? In this article, I explore risk management strategies with a particular focus on IT risk. I’ll cover key concepts like risk formula, risk matrix, risk register and risk tolerance, and reveal the five core options for responding to a particular risk. Finally, I’ll cover how you can use this understanding of risk management strategies when drafting or evaluating project proposals.

What is risk?

What exactly do we mean by risk? Broadly speaking, risk is the possibility of something bad happening. In the context of IT specifically, risk is the potential for failure or misuse of information technology to lead to unplanned negative business outcomes, such as data loss, operational disruption, customer churn, lawsuits and fines from regulators.

IT risks come in an extremely broad range of flavors, but here are some of the most common ones:

- Risk of cyberattacks — The IT risk that typically leaps to mind first is deliberate attacks. For instance, malicious actors might use phishing campaigns to plant ransomware in your network to extort payment, launch denial-of-service (DoS) attacks to crash your corporate websites or services, or steal sensitive data to sell to competitors.

- Risk of errors — Overworked, poorly trained or careless users are another key risk because they can make costly mistakes. For instance, an employee might leak sensitive data by accidentally emailing a file to the wrong recipients. IT pros pose even higher risk since they might incorrectly configure firewalls or cloud services and thereby enable cyber criminals to slip into the network, or they might expose their privileged credentials to theft by using them to log on to insufficiently hardened machines.

- Software risks— Software bugs, misconfigurations and compatibility issues can lead to costly system downtime, security breaches and business disruptions. While regular patching and updates mitigate this risk, attackers also work hard to discover software flaws and exploit them before vendors can develop fixes for these zero-day vulnerabilities.

- Hardware risks— Servers, workstations, networking equipment and other physical components of the IT infrastructure can malfunction or fail altogether. They can also be sabotaged or stolen.

- Obsolescence risks— Technology that is no longer maintained and supported is at increased risk of compromise and failure.

- Compliance risks— Failure to comply with applicable regulations and standards can result in steep fines and other penalties from regulatory bodies.

- Innovation risks— Adopting new technology solutions and processes can lead to unexpected costs to address deployment and integration challenges, or even to lost business due to poor market reaction.

- Supply chain risks— Organizations are also at risk from cybersecurity issues anywhere in their supply chain. A breach or mistake by a supplier, partner or service provider can cause production delays and compromise product quality, as well as lead to data loss and downtime.

How organizations quantify and prioritize risk

The first step in IT risk management is to assess and prioritize risk.

Risk formula

The standard formula for calculating risk is the following:

Risk = Likelihood * Severity

In this formula, likelihood is the probability that a given event will happen, while severity is the damage or impact that the organization would suffer if it did happen.

How do organizations use this risk formula? Some organizations take a quantitative approach, assigning a percentage value for likelihood and a monetary value for severity. But it’s also useful to take a qualitative approach, which is what we’ll do here.

Risk matrix

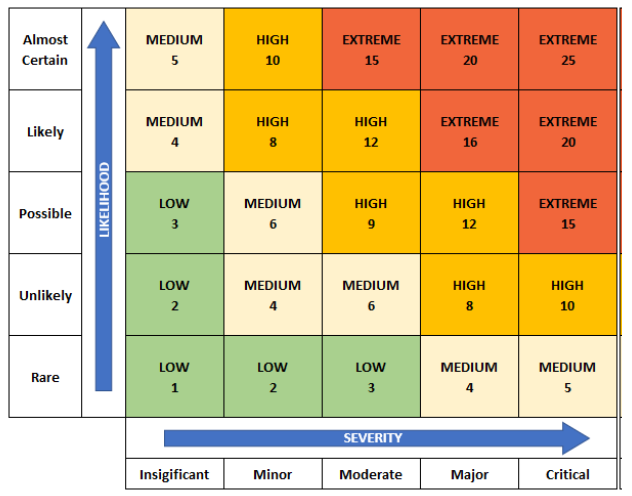

With a qualitative approach, likelihood and severity are not expressed as numbers, so risk is not calculated using the mathematical operation of multiplication. Instead, likelihood, severity and risk are all expressed as a set of discrete categories, For instance, likelihood can range from rare to almost certain, while severity is ranked from insignificant to critical.

Once the likelihood and severity of an event are assessed, organizations use a risk matrix like the one below to determine the associated risk. In this risk matrix, the possible risk values for an event are low, medium, high and extreme.

As you can see, the more likely an event is and the more critical its impact, the higher the resulting risk value. Here, risks categorized as extreme are colored red and clustered at the top right of the matrix.

On the other hand, even if an event is possible, if its impact is insignificant, the risk rating is low. Similarly, if an event is expected to occur only rarely, the impact if it did happen must be major or critical for the associated risk to be anything but low.

Inherent risk and residual risk

By applying a risk matrix like this, organizations can determine the inherent risk associated with various events. But the goal of IT risk management is not merely to measure inherent risk; it is also to strategically take action to improve the organization’s risk posture.

By implementing selected controls, processes and other measures, an organization can reduce the likelihood or severity of an event. This can yield a more acceptable residual risk. For example, implementing email filtering can reduce the likelihood of phishing messages ever reaching users, and requiring multifactor authentication (MFA) can reduce the impact from stolen passwords.

Risk register

Organizations face risk from a wide range of events. Therefore, a core best practice in IT risk management is to keep a risk register. A risk register is a record of all the risks that have been identified, along with details about how they have been quantified and prioritized. Using a spreadsheet or database for the risk register makes it easier to group and review risks, as well as to understand how a particular risk fits into the larger risk landscape.

Risk tolerance

To create a roadmap for risk management, assessing risks and assigning them to ranked categories is necessary but not sufficient. There is another critical ingredient to understand: risk tolerance, also known as risk appetite. Risk tolerance is how acceptable various risk levels are to the organization. In practical terms, risk tolerance helps organizations determine their response to the risks in their risk register.

There is no one “right” risk tolerance. One company might be fine with risks that another company finds unacceptable, just as individual investors might choose different allocations of stocks and bonds in their portfolios. A key factor in risk tolerance is the organization’s resilience to the impact of an adverse event. For example, a company that dominates a given market might not be as worried about reputation damage as a small company trying to establish a customer base.

Risk management strategies

At a high level, there are five possible responses that organizations can choose for a given risk:

- Reduction — The most obvious of the five risk management strategies is to take action to lessen the likelihood or impact of an adverse event. Many IT security controls are reduction For instance, implementing a robust patch management process reduces the likelihood of adversaries exploiting known vulnerabilities, and adopting a strong password management policy reduces the chance of user account compromise.

- Acceptance (retention) — Another option is to choose to do nothing about a given risk. Note that accepting risk is not the same as ignoring it; acceptance involves making a deliberate decision, not sticking one’s head in the sand. Acceptance is a particularly viable choice for low-risk events. For instance, organizations that are far from any ocean might decide that the inherent risk of a hurricane damaging their datacenter is too low to be worth the expense of doing anything at all in response to it. Another solid reason for choosing to accept a risk is that the costs of other options are deemed to be too high (where “too high” depends greatly on the organization’s risk tolerance).

- Avoidance — The third of the risk management strategies is to avoid the possibility of a given adverse event. For example, an organization can avoid the risk of a breach of GDPR-regulated data and the associated penalties by not collecting or processing the personal data of EU residents. And they can avoid the risk of users installing malware on their devices by never granting them the local admin permissions required to deploy software.

- Sharing — Organizations can choose to share a risk by spreading it among multiple entities. For example, organizations might share the risks inherent in delivering a particular service with a partner or subcontractor that has specialized expertise or equipment.

- Transfer — The last of the five risk management strategies is to transfer risk. The most common way to transfer IT risk is to purchase cyber insurance. With a policy in place, if an adverse event occurs, the insurance company will pay for the damage.

Not all options may be viable for a given risk. For example, some risks may be impossible to avoid, and others may not be candidates for sharing or transfer.

Blending risk management strategies

In some cases, organizations can combine two or more of these IT risk management strategies to address a particular risk. For instance, transferring risk to a cyber insurance provider can be quite expensive if the likelihood of security breaches and downtime is high. Moreover, transferring all risk is simply not feasible; insurance policies almost always have a significant set of exclusions.

Accordingly, organizations commonly use combine several risk management strategies as follows:

- Reduce inherent risk by implementing effective controls and processes.

- Transfer much of the remaining risk to an insurance company at a far lower cost.

- Accept the residual risk.

Applying risk management strategies to develop or assess projects

This comprehensive understanding of risk management strategies can be used to craft more effective project proposals and to evaluate proposals more effectively for the business. There are four elements to pay attention to.

Which risks the project will address

Which items from the organization’s risk register does the project address? Or perhaps it covers a risk that the organization has so far overlooked but which needs to be assessed, prioritized and added to the risk register?

A great way to get the necessary context here is to look at breaches and other incidents at peer companies in your industry. Learn as much as you can about the root cause and contributing factors, as well as the types and extent of the resulting damage. Then ask yourself, “How could a similar incident occur in our organization? What could we do differently to prevent it from happening or mitigate the damage?”

How the project will address those risks

Typically, IT teams focus on the response of risk reduction. But remember that the organization has other options, such as sharing, avoiding or accepting risk. The proposal should detail which risk management strategies are being proposed and exactly how they will address the risk appropriately.

It can be useful to consider several different response options that have different levels of impact on the risk and different estimated costs. This approach can help you understand the management team’s risk appetite.

Whether the proposal is proportionate to the risks it addresses

It’s also important that proposals be proportionate to the seriousness of the risk they intend to address. That means looking hard at both of the two factors that are used to assess risk: likelihood and severity. For example, a proposal to spend $10 million to reduce the risk of an event that is highly unlikely or that would cause only $1,000 worth of impact is not likely to be worthwhile.

For evidence about likelihood, severity and benefit, talk to colleagues and peers about their experiences with similar challenges. Look for articles detailing how the risk addressed in the proposal has led to costly breaches or downtime at other organizations. On the flip side, seek out case studies that demonstrate how projects with similar risk management strategies have succeeded in addressing the risk.

How the project fits into the larger IT risk management strategy

Organizations do not have unlimited funding for IT risk management strategies. Accordingly, proposals are not evaluated on their inherent merits alone; they are also weighed against other risk management strategies. Decision makers seek to prioritize projects that address critical risks — especially those that do so cost effectively.

Therefore, consider carefully how a given project will significantly improve the organization’s cybersecurity and cyber resilience posture and provide a solid return on investment. In short, does it align with the organization’s risk register and risk tolerance?

Conclusion

Every organization faces a variety of risks. IT risks range from deliberate cyberattacks and costly errors, to software and hardware risks, to compliance and supply chain risks. Developing effective risk management strategies requires a solid understanding of how to measure, prioritize and record risks, as well as the five core options for responding to them: reduce, accept, avoid, share or transfer. With this information, organizations are better positioned to make well-reasoned decisions that improve their cybersecurity and cyber resilience.